Pandemic. The word originates from the Greek word pandēmos – meaning from ‘all’ (pan) ‘people’ (dēmos).

Many parallels have been drawn between the current COVID-19 pandemic, which stands for Coronavirus Disease 2019, and the 1918 Spanish Flu, which killed an estimated 500,000-675,000 people in the U.S.

Despite its name, the Spanish Flu did not originate in Spain. The first known case was reported in Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 11, 1918. Spain was neutral in the First World War and did not censor its press. Thus, it was one of the only countries reporting on the pandemic at the time and thought to be where the outbreak began in 1918 as a result.

Young soldiers and sailors massed at military camps in the U.S., sailed for Europe on ships stuffed to the gunwales with humanity, fought side by side in the trenches and came home in victory to adoring crowds. The toll was enormous, on them and the people they infected. The Spanish flu could just as easily have been called the U.S. Army or U.S. Navy flu instead. Or the German or British flu, for that matter.

When packed boatloads of American soldiers shipped out, the virus went with them. By May 1918, a million Americans had landed in France, and influenza soon blazed across Europe. It directly impacted the war, as more than 200,000 French and British soldiers were too sick to fight and the British fleet was unable to weigh anchor in May. More U.S. soldiers died from the 1918 flu pandemic than were killed in battle during World War I in 1918. With summer, the 1918 flu seemed to subside. But the killer was merely lying in wait, set to return in the fall and winter typical peak flu season more lethal than before.

Social Distancing works…for a while

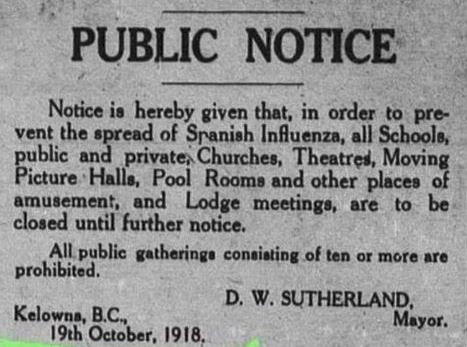

The situation with the 1918 flu was so dire that many cities mandated quarantines and social-distancing measures. In San Francisco and Seattle, laws were passed forcing people to wear masks covering their mouths and noses while in public. The public health commissioner in Chicago told police to arrest anyone seen sneezing without covering their face in public.

The 1918 pandemic killed an estimated 500,000-675,000 people in the U.S. Yet its effects varied between cities – those that went into lockdown fastest were most effective at reducing the death rate, according to a 2007 research paper. St. Louis, for example, implemented a relatively early, layered strategy that included school closures and the cancellation of public gatherings. It sustained those interventions for about 10 weeks and did not experience nearly as harmful an outbreak as 36 other communities.

In September 1918, as the 1918 flu’s second and by far deadliest wave hit in the U.S., Philadelphia’s public health chief disregarded advisers and let a massive war-bond parade proceed through downtown. The H1N1 virus raced through the masses in what has been called the world’s deadliest parade. As officials insisted there was nothing to be alarmed about, people were seeing neighbors sicken and die with astonishing speed and mass graves being dug. “It’s just the flu” had worn thin as the mantra of officialdom.

Within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was filled. In the week ending October 5, some 2,600 people in Philadelphia had died from the flu or its complications. A week later, that number rose to more than 4,500.

Late that November, sirens wailed in San Francisco to sound the all-clear after six weeks of lockdown and tell people they could remove their masks. San Francisco, like many cities in the West, had been largely spared the first wave and spent the interval preparing for Round 2, mandating masks and jailing people who didn’t comply.

The precautions paid off with a death rate lower than in afflicted cities elsewhere. But the city relaxed too soon. In December, thousands of new cases erupted. San Francisco’s death toll mounted by more than 1,000.

A research paper published in 2007 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined 17 U.S. cities during the 1918 flu pandemic. It found that cities in which interventions were implemented early had peak death rates about 50% lower than those that did not. It concluded that social distancing and other measures “can significantly reduce influenza transmission, but that viral spread will be renewed upon relaxation of such measures.”

The researchers examined social distancing in 43 cities during about 24 weeks in 1918-19. Public gathering bans typically meant the closure of saloons, public entertainment venues and sporting events. Indoor gatherings were banned or moved outdoors.

In Atlanta, the mayor sided with the business community and ended closures after three weeks, despite objections from the board of health. The epidemic raged in Atlanta.

Researchers documented public pressure to end social distancing as soon as the flu seemed to peak and ebb. Cities then lifted the measures, and people lined up for movies and packed into dance halls and shopping districts. The result? Cases and deaths resurged. Most cities closed their schools once again.

A recent paper co-authored by Marc Lipsitch, a Harvard epidemiologist, in Science suggested that a single period of distancing could not permanently solve the problem; prolonged or intermittent social distancing may be necessary into 2022.

History Repeats

The 1918 pandemic had profound impacts on life in the United States. By October of 1918, some 195,000 Americans were killed by the outbreak. By the time it ended, over 600,000 had lost their lives. To date the approximate number of deaths from COVID-19 is over 140,000 in the United States.

Modern science quickly identified today’s new coronavirus, mapped its genetic code and developed a diagnostic test. That has given people more of a fighting chance to stay out of harm’s way, at least in countries that deployed tests quickly, which the U.S. did not.

But the ways to avoid getting sick and what to do when sick are little changed. The failure of U.S. presidents to take the threat seriously from the start also has history repeating itself.

President Woodrow Wilson’s principal failure during the 1918 pandemic was his silence. Not once, historians say, did Wilson publicly speak about a disease that was killing Americans, even though he contracted it himself and was never the same after.

In April 1919, President Wilson fell deathly ill in Paris with the flu. “At the moment of physical and nervous exhaustion, Woodrow Wilson was struck by a viral infection that had neurological ramifications,” biographer A. Scott Berg wrote in Wilson. “Generally predictable in his actions, Wilson began blurting unexpected orders.” Never the same after this illness, Wilson would make unexpected concessions during the talks that produced the Versailles Treaty.

John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza.” was enlisted 15 years ago in a Bush administration drive to prepare all levels of government for pandemics. The intent was to respond early, relax cautiously, and tell people the truth. Instead he has seen denial followed by a chaotic federal response and leadership vacuum as Washington and the states compete for the same medical essentials and now move fitfully toward reopening. President Trump all but declared victory before the current infection took root in this country and he’s delivered a stream of misinformation and misguided directives ever since.

What about the economy?

According to a recent paper by two Federal Reserve economists and an MIT professor, those cities that put lockdown measures in place soonest did not have adverse economic impacts over the medium term. The researchers concluded: “Cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively do not perform worse and, if anything, grow faster after the pandemic is over. Our findings thus indicate that NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions) not only lower mortality; they may also mitigate the adverse economic consequences of a pandemic.”

Eric Toner is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and a world leader in pandemic preparedness. “There is no way to completely stop this,” says Toner. “It can’t be contained. It can only be slowed down. But slowing it down is essential and requires an unprecedented level of action. “

Until we have treatments for the disease (which could take three to six months) or a vaccine (which could take one to two years) the solution to fighting this pandemic is decidedly lo-tech: Stay at home.

“We all have to band together to do social distancing, to adhere to these really difficult public health interventions that are changing our lives so dramatically. We have to do this for the good of our neighbors and our family members and our communities.”

It’s actually pretty straightforward. If we cover our faces, and both you and anyone you’re interacting with are wearing a mask, the risk of transmission goes way down. Being outside, having distance between you and other people reduces the risk of transmission dramatically.

“There are a lot of things you can do and maintain those conditions. If you spread out, if you maintain distance, if you avoid crowded places, you could go to a beach, you go to the mountains, you could go to a lake, you can do things outside without a problem.” As for those who refuse to wear a mask, Toner doesn’t mince his words. “They will get over it,” he says. “It’s just a question of how many people get sick and die before they get over it.”

Post Pandemic Optimism

If there’s anything to give us some comfort in the current crisis, it’s the reminder that the world has survived a pandemic before. My grandfather survived the 1918 flu pandemic to live a long and storied life.

And then there was The Roaring Twenties. This was a period of economic growth which emerged from the aftermath of the 1918 flu pandemic and World War I, as people who had endured both catastrophic events reached a renewed sense of optimism. This decade of the 1920s saw a huge surge in wealth, innovation and change, as Americans began a spending spree which stimulated the blighted economy. Positive changes in society included women’s suffrage, which saw women gain the right to vote in 1920, and a cultural boom in jazz music and dancing during the 1920s. We’ll need to be patient to see our version of improved life that will follow this current pandemic, but what stories we will have for our grandchildren provided we survive.