Much has been written about the Civilian Conservation Corps (“CCC”). I wanted to write about a little part of this program that helped shape my grandfather’s life.

The events that led to the formation of the Civilian Conservation Corps started in the 1920s and culminated in the Great Depression of 1929 and the years following. During The “Roaring ’20s” technological advances meant that as many as 200,000 workers lost their jobs to automatic or semiautomatic machinery.

Throughout the 1920s, the value of farmland dropped 30-40%. Severe droughts on the Great Plains in the early 1930s, coupled with migrating hordes of ravenous grasshoppers that stripped the fields and trees bare, caused tremendous dust storms and virtually halted all agricultural endeavors. By 1933, when Franklin D. Roosevelt entered the White House, around 9,000 banks had failed, nearly 25% of the total labor force was unemployed, and nearly a million farmers had lost their land when banks foreclosed. (Illinois Department of Natural Resources)

In what would later be called “The Hundred Days,” President Roosevelt revitalized the faith of the nation by setting in motion a “New Deal” for America in 1933. One of these New Deal programs was the Emergency Conservation Work (EWC) Act, more commonly known as the Civilian Conservation Corps.

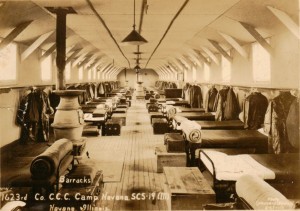

The CCC was modeled on the military, minus the guns. Enlistees wore uniforms left over from the Great War (World War I), were stationed in military-style barracks, and were even supervised by military brass.

The Army mobilized the nation’s transportation system, and moved thousands of enrollees from induction centers to working camps which would be located next to railroad lines. It used regular and reserve officers, together with regulars of the Coast Guard, Marine Corps and Navy to temporarily command companies. About 3.5 million men served in the CCC. Employment was divided into 6 month enrollment periods.

William Clarence Irwin, my grandfather, was one of the men who enlisted in the service of the Civilian Conservation Corps. The notes in my genealogy files indicate he went into service with the CCC in late 1934 or early 1935. I am not certain of his complete service yet, whether 6 months or a year. In 1936 he was no longer enrolled in the CCC, but began using skills he likely learned while in service to build a log cabin with a two-story rock fireplace in his home community. That structure was known as “The Country Home” just outside of the town of Golconda, Illinois, and served as a community gathering place, a restaurant, and a home for his family. I will elaborate on that in another post to this blog.

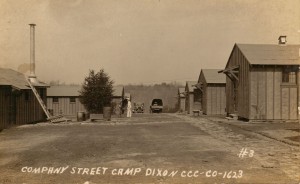

W.C. Irwin began his enrollment in the Civilian Conservation Corps in Pope County, Illinois, at Camp Dixon Springs. Records show this Camp was designated as SCS-1, Company D-695 of the CCC. The “SCS” indicates this was a USDA Soil Conservation Service work camp.

This Camp began field work November 1, 1934, and ceased fieldwork September 30, 1937. The Photo of Camp Dixon on the left describes this as CCC Company 1623.

Since enlistment terms were for 6 months, W.C. Irwin may have re-enrolled due to the fact that he was later at Camp Havana, in Mason County, Illinois.

Camp Havana was designated as SCS-19, Company 1623 of the CCC. Fieldwork from this camp began May 24, 1934, and ceased September 28, 1937. The project from Camp Havana was designated PE-53, a Private Land Erosion project. Camp Havana was in the town of Havana, the County Seat of Mason County, Illinois, located on the Illinois River in the west central part of the State.

I found information about the camp identification codes and CCC history on the Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy website.

The CCC legacy can be found all over Illinois, from the wilderness roads and trails blazed by enlistees to the shelters and cabins they built and to the lakes they created and forests they planted. In some instances the CCC also worked on private tracts, such as in the case of existing drainage districts.

Some larger Illinois state parks had long-term or multiple projects. Several other state parks received improvements with CCC labor, including the development of a state tree nursery near Havana in Mason County, Illinois. Forest rebuilding and erosion flood control were just some of the activities of the CCC. Roads and buildings were constructed by the men in these work companies.

In addition to their cash stipend for the five-day workweek, the young men received three full meals a day, lodging, clothes, footwear, inoculations and other medical and dental care, and, at their option, vocational, academic, or recreational instruction.

The following paints a typical day as described on the website of The Association of Retired Conservation Service Employees (ARCSE)

“Every workday (Monday- Friday) the boys arose to reveille at 6 am, cleaned up and dressed, policed the grounds, formed for the flag raising ceremony and roll call, ate a breakfast of things like fruit, cereal, pancakes, eggs, ham, coffee, and then made their beds and cleaned their barracks before heading off to their worksites at 8 am. Remember, camps were run by Army Officers!

The boys planted trees (the CCC was also known as Roosevelt’s Tree Army), built roads, bridges, fire lookout towers, telephone lines, cabins, picnic shelters, etc. They fought forest fires, performed archeological digs, installed conservation measures, etc. The work day ended at 4 PM.

They were given time to clean up and get in dress uniform for supper. The supper hour was around 5 PM with plenty of plain but filling food. The average enrollee gained about 20 pounds (mostly muscle). After dinner and weekends were free time. The boys were encouraged to improve their literacy and vocational skills in their free time. Educational classes were optional but encouraged.

The classes and training offered to the men broadened their intellectual horizons and employment opportunities. On the job training was also very valuable to the enrollees. Vehicle repair, carpentry, soil conservation, drafting, electrical wiring, and accounting are examples of common opportunities, since most camps used these skills on a daily basis. “

In Southern Illinois, the CCC planted thousands of trees, installed telephone lines, and built recreational areas, picnic facilities, impoundments, roads, and trails. The CCC was critical in the development of Shawnee National Forest, which was created in 1933.

Some of this information came from an article on the Illinois Times website.

A good resource for genealogists to research records of the Civilian Conservation Corps can be found from Diane L. Richard and the Archives.

Here is a link to the Guide to Federal Records of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) on the National Archives website.